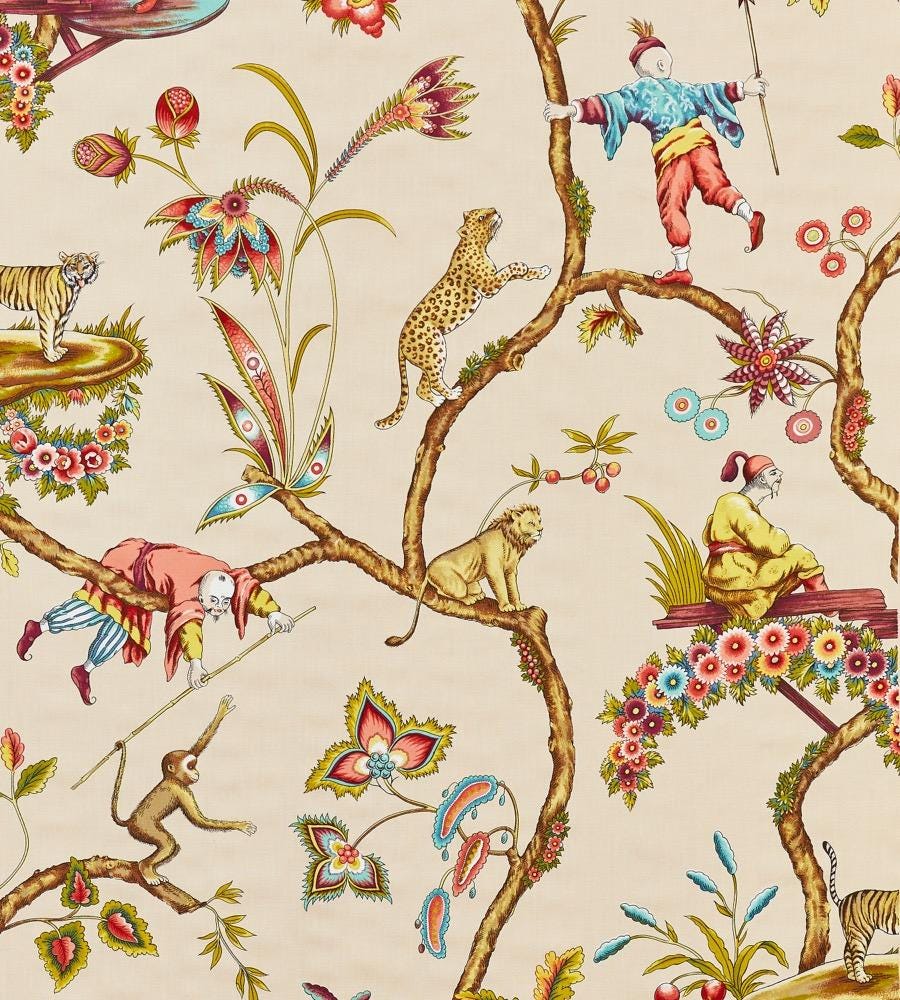

Five years ago, I was beginning a new role as a design director for a ninety-year-old heritage textile company. My colleagues and I were meeting to select archival patterns for a future collection, one of which was called “Chinoise Exotique.” The print featured four costumed Asian men cavorting with lions, tigers and monkeys in an airy, stylized jungle. I understood that this was an example of chinoiserie, a popular decorative style co-opting Asian motifs in Western art, furniture and architecture dating back to the 17th century. But as I studied the simpering expressions and jester-like outfits of the figures, I couldn’t help but cringe.

My heartbeat quickened as I told my coworkers I thought the pattern was “kind of racist.” Saying “kind of” did not soften the presence of the word “racist,” which hung in the air like a putrid smell.

They all stared at me, the new hire, and the only person of color in the room.

“But it’s classic,” someone said, and another person agreed.

I realized that though we were looking at the same design, we saw different things. To my colleagues, Chinoise Exotique was a beloved bestseller, safeguarded by tradition and untouched by any larger cultural conversation. For me, the pattern represented outdated caricatures and antiquated style. Those little figures were like distant ancestors reminding me that I wasn’t supposed to be here, not on this side of the table.

Only a few generations ago, my South Asian ancestors were harvesting sugarcane under British colonial rule in Guyana, South America. If the course of my family’s history had gone even slightly differently, I too would’ve been a laborer or servant to the ruling class, either in India, Guyana, or even in New York City, where many of the Guyanese people I met were doormen and nannies.

Building on the legacy of my grandmothers, who were both skilled seamstresses and designers in their own right, I attended art school and forged a creative career. Despite the skepticism of my family and community, I was, against all odds, successful in a way I’d never expected. With this success came access to a world in which patterns like Chinoise Exotique were considered beautiful without question.

It was one thing to study examples of chinoiserie as a part of textile history, but it was another thing to choose this pattern among infinite possibilities and bring it to market in the 21st century. As a descendant of the colonial legacy, I struggled to embrace a pattern that kept its subjects in captivity, dancing up the walls of a Park Avenue penthouse just as they had adorned the halls of an 18th century aristocrat.

There were so many incredible designs to put into the world - why spend our budget on this one?

Year after year, I continued to push back and dialogue with the team. One afternoon, I asked my colleagues if they thought it would be acceptable if the characters in the design were Black. Thankfully, everyone shook their heads “no.” This seemed like an “aha” moment. If they could understand the boundaries of representation for one group of people, surely they could see how depicting Asians was just as problematic.

I thought I’d made a breakthrough, but it wasn’t long before the requests resurfaced. The demand for this style of pattern was strong among our one-percenter clients. No matter how passionate or convincing my argument, the design would sell and we all knew it.

But every time I pulled out Chinoise Exotique and similar archival designs to work on the recolorations, I felt nauseous. Rather than studying the designs from a technical perspective, analyzing color relationships and specifying new palettes, I found myself in communion with the characters, forever fetching water, playing with wild animals, and wandering in and out of pagodas. I didn’t want to select a swatch for their skin color, deciding just how yellow or brown they would be. I didn’t want to stare into their blank eyes and Fu Manchu mustaches. I wanted to break free of this version of “normal” and make something new.

Chinoiserie originated at a time when very few Europeans could travel, and Asia was a quasi-mythical landscape to be imagined. Not all chinoiserie patterns are problematic, but the figurative designs tell a specific story essentially rooted in an ignorant vision of the non-white world.

I’ve since moved onto a different company in the luxury home furnishings industry, but I haven’t escaped this conversation. Archival chinoiserie patterns are on every bestseller board and studio table. The printed figures pose in their exotic gardens, and together, we remain stuck in time.