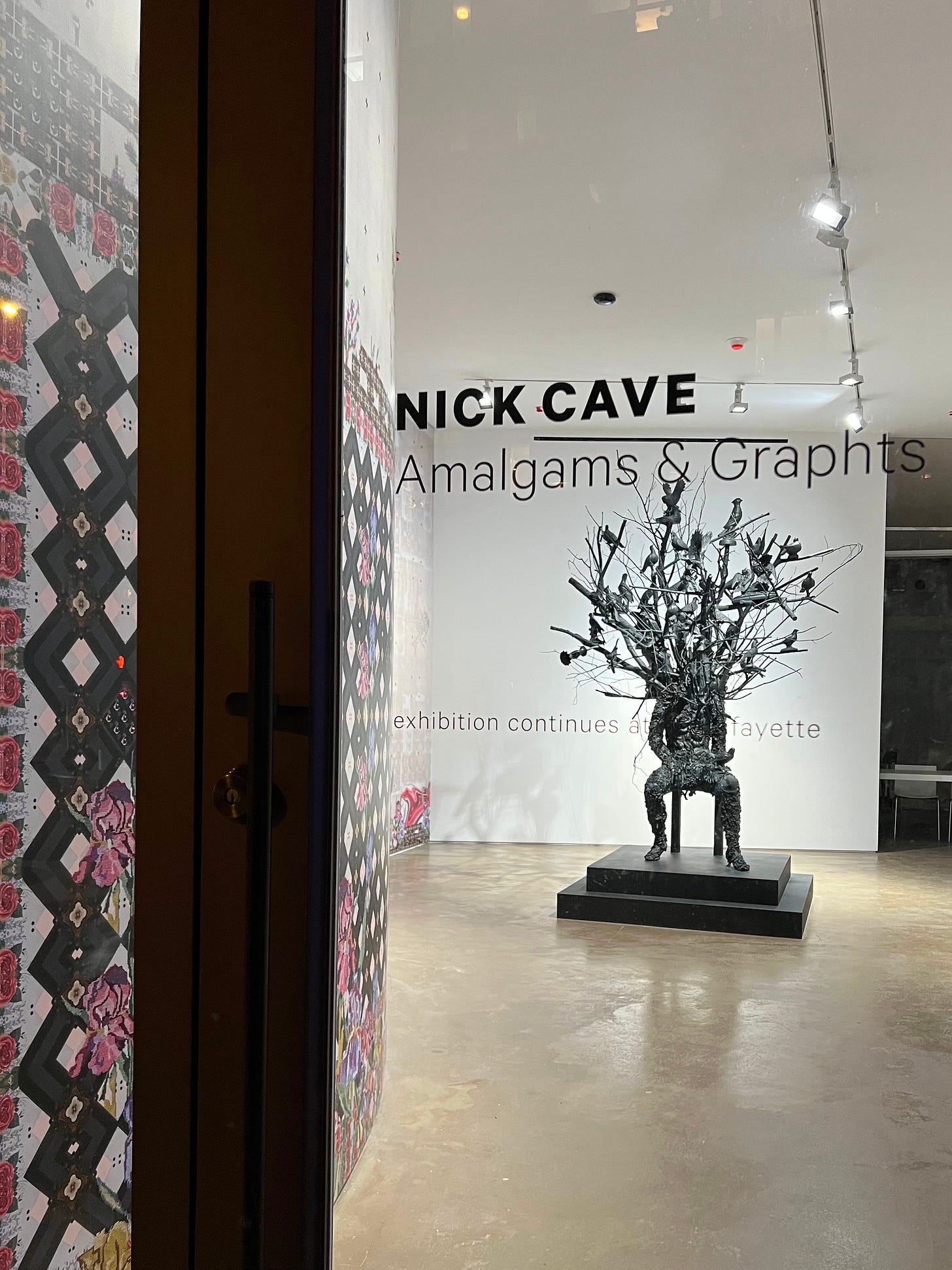

A few weekends ago, I went to the new Jack Shainman Gallery in Tribeca to see the latest exhibition by artist Nick Cave titled, “Amalgams & Graphts.” Having seen Cave’s epic retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in 2022, I knew it would offer much needed inspiration.

Motivated less by a desire to be a cultured mom and more by not wanting to pay for childcare, I brought my kids, lured by the promise of brunch. On the way, we had a conversation about not touching the art (we almost got kicked out of MoMA when Zadie tried to hug a Mike Kelley sculpture), and not embarrassing me in public. Bacon would be their reward for good behavior. With the ground rules set, we were ready to enjoy the show.

Cave was best known for his Soundsuits, sculptures he created in response to the beating of Rodney King by four law enforcement officers in LA in 1992. The suits functioned as a kind of armor, obscuring the wearer’s identity in an otherworldly disguise. Using a range of textile techniques, these intricate creations transformed familiar materials into sublime sculptural forms worn by the artist in live and video performances.

In his latest exhibition, Cave continued his exploration of the body with three bronze sculptures titled Amalgams. The largest piece was Amalgam (Origin), a nearly 26-foot sculpture occupying the center of the gallery. Part man, part tree, the figure had a mythological presence, a deity from another realm. The surface was engraved with a dense, three-dimensional garden rippling with detail. In place of a head, a network of branches laden with birds emerged from its shoulders, reaching to the coffered ceiling. A friendly gallery attendant told the kids how they’d had to take out a window and use a crane to bring the piece into the building.

“It’s like a superhero,” Miles commented as we stood at the base peering upward.

There was something protective in the stance of Amalgam (Origin). It made me think about my ancestors, and the wise old tree characters in books and movies. In its outsized, surreal way, the piece was a reminder of the inextricable bond between humanity and nature, one form merging with the other. If I was looking for a sense of awe on a bleak winter’s day, I found it.

Behind this central sculpture lay Amalgam (Plot). In this piece, two bronze figures were on the ground, their bodies splayed, their heads obscured.

“I think they’re dead,” Zadie observed, her dark eyes solemn.

She was right. The piece was taken from a still of a video of a brutal incident. From one figure emerged a wild garden of tole flowers, or decorative metal flowers painted to look realistic. I couldn’t help but assign the metaphor of hope onto this golden patch. In the aftermath of unforgivable acts of violence, growth was still possible.

Graphts was a new series of mixed media assemblages juxtaposing needlepoint portraits of the artist with vintage serving trays. Richly colored and tactile, each composition played with structure and borders, the seams punctuated by visible nailheads. While needlepoint was associated with upper class gentility, the trays, painted with lush floral bouquets, were symbols of servitude. These layers of history were in dialogue with Cave himself, pictured for the first time in his recognizable form.

The artist, who is one of seven boys, grew up in Fulton, Missouri in a tightly knit community. In an interview on Art 21, Cave spoke about him and his brother Jack being the two creatives in the family.

“We grew up learning, being immersed in making things out of nothing. Because we were not privileged, I was making stuff out of whatever was around…I think about my grandparents and the values they placed within the family structure. They were makers and builders, and I’m celebrating that along with ideas that are associated with craft.”

Later, Cave’s practice was further shaped by his experience of being the only minority as graduate student at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1988.

“It was difficult because it was the first time that I was confronted with my identity as a Black male. Prior to arriving at Cranbrook, it never entered my mind or my existence, and I never thought that I would be the only minority student there. I tried to understand what that meant, by making a series of drawings about my identity. It was a lot to work through, but it gave me something to respond to, right away.”

In contrast with this isolating experience, Cave opened Facility in 2019, a multidisciplinary arts space he shares with his brother, Jack Cave, and his longtime partner, Bob Faust. Conceived as an incubator for collaboration, Facility is a place of community and creation, providing scholarships and opportunities for young and emerging artists.

As Miles, Zadie and I made our final lap around the exhibition, I thought about the many layers in Cave’s work, the social and political commentary, and his evolving inner monologue. At 66 years old, he had been navigating these conversations for decades - an impressive feat for any artist

We left the gallery just as the kids started to get restless and hungry. For all intents and purposes, the outing was a success. I got to see some art, and they got to eat bacon. In the daily game of balancing my own needs with theirs, we were winning.

Nick Cave’s “Amalgams & Graphts” at the Jack Shainman Gallery is on view until March 29th.

Thank you for reading!